READ

READ

Enclothed Cognition: where science meets fashion, developing a personal style and dressing from the inside out

Many of us are sleepwalking from trend to trend, answering to an algorithm you can never truly catch up to and hurtling towards fashion burnout as a result. It’s both unsustainable and harmful to the planet and our wallets, but science suggests it could also be having a detrimental impact on our minds…

Every day we’re bombarded with ‘blink and you miss it’ micro-trends, endless ‘cores’ and mountains of fast fashion hauls passing in and out of our feeds before dissolving as quickly as our attention spans. We’re consuming fashion faster than we ever have - and we’re about to fold in on ourselves. Just a few months into 2024 and the trend machine already spat out the ‘eclectic grandpa’, the ‘mob wife’, ‘office siren’ and even ‘commuter core’. More trends are popping up in the last month than there used to be in 20 years. Items I wore less than a decade ago have whizzed back onto Pinterest boards (American Apparel, I’m looking at you!) and soon enough, what we wore last week will be considered vintage. It’s a serious case of fashion whiplash.

Diagnosis: fashion burnout

Many of us are sleepwalking from trend to trend, answering to an algorithm you can never truly catch up to and hurtling towards fashion burnout as a result. It’s both unsustainable and harmful to the planet and our wallets, but science suggests it could also be having a detrimental impact on our minds. The power of clothing has long been dismissed as something two-dimensional and frivolous. After all, those in the industry have had to fight for fashion to be considered a legitimate art form, having never been held in the same esteem as paintings, sculptures or music. It’s no wonder many would think the worlds of science and fashion could never collide, as it shatters the notion that what we wear runs deeper than just a hollow aesthetic. Fashion and science are unlikely neighbours but the concept of ‘enclothed cognition’ says otherwise. It could be the medicine our wardrobes desperately need to be prescribed.

Just what the doctor ordered

Enclothed cognition is a term coined by researchers Hajo Adam and Adam D Galinsky in 2012 which explores the systematic influence that our clothes have on how we feel, behave and see the world. As part of their experiment, Adam and Galinsky used a lab coat to examine how the wearer was impacted by a clothing choice synonymous with intelligence and attentiveness by having them complete an attention-based task while sporting it. The results were staggering - in the first test, physically wearing a lab coat increased selective attention compared to not wearing one. Meanwhile, in the second and third tests, wearing a lab coat described as a doctor's coat increased sustained attention compared to wearing a lab coat described as a painter's coat.

What does this mean?

The phenomenon injects a new layer of importance into the ‘trivial’ act of getting dressed. We know that mindful dressing can boost our self-esteem, but enclothed cognition tells us the symbolic meaning and physical experience of wearing garments have the power to alter our perception and behaviour.

While I imagine many of us aren’t likely to go out rocking a lab coat and goggles (I can already hear the TikToks Gods whispering, “Bunsen burner core!!!”), we can still use Adam and Galinsky’s theory as a springboard to truly dressing from the inside out, making better choices for our wardrobe and the planet and emerging from the other side with a more concrete sense of personal style.

Speaking to Studio V., therapist Sophie Cress LMFT explained that enclothed cognition ‘highlights the significant impact that fashion may have on our psychological experiences as well as the significance of dressing according to our own tastes and moral principles’, adding that this ‘emphasises the complex interplay between our interior states and outward appearance’.

Stepping off the hamster wheel

That’s not to say everything in the fashion social media space is bleak. The rise of TikTok fashion amid the pandemic has also proven to be a catalyst for people reevaluating their relationship to consumerism. Indeed, people are stepping off the fast fashion hamster wheel in their troves and adopting a more ethical and sustainable approach to consuming fashion and curating a capsule wardrobe. ‘Dopamine dressing’, for instance, is just one buzzword swirling around our TikTok feeds, a seemingly natural branch of enclothed cognition in the real world emphasising the importance of choosing garments that spark joy as opposed to mindlessly following trends that may not resonate with us.

It’s understandable why so many of us have been caught in the net of microtrends - it’s natural to yearn for a sense of belonging, something further accelerated during those hazy lockdown days - but there are ways we can claw our way out by stepping back and harnessing the power of our wardrobe.

After all, even science agrees.

Shopping from your own wardrobe and finding new ways to restyle your clothes, avoiding forcing trends into your collection for the sake of being ‘in’, upcycling existing pieces and curating key, reliable staples for your other pieces to orbit are just a few ways experts recommend building your personal style. And of course, shopping intentionally and ethically, too. That’s not to say we can’t cherry-pick things we see online that resonate with us, but ultimately, racing to keep up with trends does nothing good for the planet or our mental well-being.

Cress explains: “People can purchase clothing more thoughtfully if they are aware of the ways that it affects their mood and conduct. Choosing clothes that not only make us feel good but also support ethical and sustainable methods can enhance our shopping experiences and encourage greater social and environmental responsibility.”

What we wear is far from trivial. Our wardrobes are treasure troves of unused potential to harness the mood our clothing evokes and develop a signature style that truly expresses who we are - not just a mirror image of fast fashion ‘new in’ pages and yo-yo-ingyo-yoing TikTok algorithms.

Now, that’s certainly one way to look at retail therapy.

WRITTEN BY CHLOE ROWLAND.

Hysteria: Schiaparelli and Madness

Surrealism loved insanity. Freudian psychology drew a distinction between the conscious and subconscious mind, a differentiation which was a cornerstone of the Surrealist movement. The work of Salvador Dalí, a ubiquitous surrealist artist, contained many depictions of what Sigmund Freud considered to be ‘fetish objects’, and the erotic subconscious was a prominent underlying theme to…

Written by Emily Poncia

Surrealism loved insanity.

Freudian psychology drew a distinction between the conscious and subconscious mind, a differentiation which was a cornerstone of the Surrealist movement. The work of Salvador Dalí, a ubiquitous surrealist artist, contained many depictions of what Sigmund Freud considered to be ‘fetish objects’, and the erotic subconscious was a prominent underlying theme to Surrealist work. The complex and nonsensical artworks sought to expose the sub-conscious mind: ‘the authentic voice of the inner self’.[1] Surrealists believed that the curing of madness was a wrongful attempt to conform to conscious normality and that the insane mind created its reality and was content.

‘Hysteria’, a specifically female brand of madness, became de rigour in this psychoanalysis-crazed zeitgeist. The concept of ‘hysteria’ was not new in the 20th century. The term was coined by Hippocrates in the 5th century BC, derived from the Ancient Greek word for uterus: hysteron.[2] Manifesting throughout the Middle Ages as both a medical condition, and a spiritual deficiency, ‘hysteria’ was cited as the cause of such wide-ranging issues as the Salem Witch trials, and infertility. However, the Surrealists latched onto Freud’s novel understanding of ‘hysteria’ developing because of frustration linked to the Oedipal complex, recasting ‘hysteria’ as a result of shocking Freudian revelations of perverse sexuality.[3]

Women diagnosed with this disease were therefore objects of sexual fascination. Images of scantily-clad ‘hysterics’ in contorted positions became both evidence of the sub-conscious mind and erotica which played into established notions of the female mind as weaker and susceptible to ailments. This fascination with a gendered model of madness which rendered women vulnerable was often explored in Surrealist art.

Surrealist artist and fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli’s practice wove together hysteria with an intuitive understanding of the subjection of the female body to scrutiny, creating a version of hysteria which gave women much more agency than the sexualised works of other Surrealists. Through creating clothing which played on the idea of the insane, Schiaparelli gave women control over their characterisation; to be seen as mad became a choice, rather than a gendered predisposition. Women’s bodies became the canvas to show off insane artworks, rather than their subject.

Moreover, Schiaparelli explored her understanding of her mind through the clothing which she created. Forming the alternative persona of ‘Schiap’, Schiaparelli spoke of a fragmentation of herself: ‘I merely know Schiap by hearsay. I’ve only seen her in a mirror. She is, for me, some kind of fifth dimension.[4] Her understanding of herself as at once actor, spectator, and narrator betrayed an understanding which paralleled the Surrealist model of the contradictory conscious and sub-conscious minds. And yet this fragmented self which Schiaparelli described did not expose her to vulnerability. Rather, Schiap was a figure through which she exercised her creative energy; her boutique in the Place Vendome in Paris was dubbed the ‘Schiap Shop’. Moreover, the bottle of her fragrance ‘Shocking’ was modelled on the bust of Mae West, a celebrity sex icon of the era. Rather than being put directly on display, the perfume was housed in an opaque fuchsia box away from prying eyes. Through the colour which came to be known as ‘Shocking Pink’, Schiaparelli laid bare society and Surrealism’s fascination with the female body through the other extreme of hiding it away.

In her clothing, Schiaparelli’s ‘hysteria’ manifested in making apparent what was not there: her original Trompe l’Oiele jumpers gave the wearer a pierced heart or large bow tie. The 'Bow Knot’ sweater featured in the Christmas Edition of Vogue 1928 initially blew Elsa Schiaparelli into the public eye. Vogue has dubbed the technique used to create this effect ‘frottage’, playing on the word’s sexual connotations, which although never explicitly commented on by Schiaparelli, again link the sensuality of the female body to the absurd and surreal.[5]

In her later career, madness manifested itself through Schiaparelli’s accessories. Jean Clement visualised Schiaparelli’s surreal designs for jewellery and accoutrements such as buttons. A necklace of metal bugs suspended in rhodoid plastic from the 1938 Autumn Couture collection, as well as clasps styled like lobsters, were a direct reference to the Surrealists’ use of the natural world.[6] In particular, the lobster motif was used extensively and eroticised by Dalí, coming to form the central motif on a dress from Schiaparelli’s Summer 1937 collection. Again, madness and female sexuality are married; a bright red lobster hovers over the genitalia of the wearer, a reference to Dalí’s Minotaur sculpture which gave voice to the shameful basal urges of the subconscious.

‘Everything which works at Schiaparelli works when the New World starts talking to the Old World and the Old World answers back’ - Daniel Roseberry

Since becoming Creative Director of the fashion house in 2019, Daniel Roseberry has invigorated Schiaparelli with the Surrealist madness and bold female sensuality of its namesake particularly poignant on the centenary of Surrealism’s original manifesto by André Breton in 1924.

Despite having previously avoided the lobster as too obvious a reference to the Surrealist origins of the house, Roseberry’s SS24 collection featured imaginative uses of the motif. In a monochrome cream look, a shirt with long sleeves and dramatic cuffs is tucked into a gathered skirt. The gathers are arranged in such a way that it appears as though the large cream lobster, positioned over the crotch, has climbed up the model’s body; Harper’s Bazaar described it as though the lobster is on the brink of exposing the model’s pants.[7]

This look is clearly sensual.

The model’s feminine curves are emphasised by the skin’s gathering as was repeating Elsa Schiaparelli’s eroticised lobster and positioning it over the erogenous zone. The shirt is roomy, and the top is left open, highlighting the model’s décolletage and portraying effortless sexuality. This highly feminine, highly powerful, and yet entirely mad model of the Schiaparelli woman has been a theme of Roseberry’s tenure with the brand. His SS22 Haute Couture collection was built around the concept of a space goddess, featuring highly sculptural uses of the metal wound into otherworldly shapes. Everyone saw the metal lungs he created, these were accompanied by such items as golden gloves which glittered and snaked their way up the model’s arms, and patent black shoes with golden toenails crowning their ends.

Roseberry has taken the hysteria which fed into the original Surrealist conception of the subconscious mind and brought it into the 21st century in the form of glistening yet absurd visions of femininity. 2024’s Schiaparelli is ‘freaky and weird and sexy’ in the same way as its 1927 counterpart, representing the importance of hysteria in establishing, and continuing, the brand’s identity.

References:

1] Watt, Judith. Vogue on: Elsa Schiaparelli (2012), (London: Quadrille Publishing Limited), 21.

[2] Tasca. Cecilia, Mariangela Rapetti, Mauro Giovannie Carta, and Bianca Fadda. “Women and Hysteria in the History of Mental Health.” Clinical practice and epidemiology in metal health 8, no. 1 (2012): 111.

[3] Ibid., 115.

[4] Dieffenbacher, Fiona. “ ‘Shocking!’ The Surreal World of Elsa Schiaparelli. Musée Des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, France, July 22, 2022 – Januart 3rd 2023.” Fashion Theory 27, no. 6 (2023): 889 – 900.

[5] Vogue on: Elsa Schiaparelli.

[6] Vogue on: Elsa Schiaparelli.

[7] Gonzalez, T. “Schiaparelli’s Lobster Skirt is a Real Fashion Delicacy.” Harper’s Bazaar. September 29, 2023. https://www.harpersbazaar.com/fashion/fashion-week/a4539571/schiaparelli-spring-2024-lobster-dress/.

The History of UK Jazz: The National Jazz Centre Scandal, Melody Maker, Benny Goodman, Kamasi Washington and more…

With Brick Lane Jazz Festival beginning today I thought I’d post this article written by Daisy Sells on my website ahead of its official publication in Issue Three, May 2024: Mental Health Awareness Month (available on May 1st). Photography by Elisa Mazzuca. Enjoy :))

Written by Daisy Sells.

I can chart my experience with jazz back to just a handful of experiences. Hearing Louie Armstrong at my Grandfather’s house, a Herb Ritts portrait of Dizzy Gillespie on my Mum’s dining room wall or a lazy Saturday gig of my Godfather’s band, The Red Hot Chillies Jazz Band (with an uneasily familiar name, I would later discover.) and all the way to live folk-jazz in a Cornish pub last week followed by a Podcast about Jacob Collier on the long drive back to London.

When I received this assignment, writing about the history of jazz on the UK music scene, I knew the institutions and individuals that I wanted to include. I have watched gigs in, written about, admired and worked for many of them and I have always been incredibly passionate about supporting and championing them come what may. But jazz also has a darker side that I had not predicted. Having visited The Jazz Centre UK, I discovered that back in the 80s the opening of the UK’s ‘National Jazz Centre’ had been shrouded in scandal as, after just three years, the Floral Street venue and almost three million pounds worth of public funding from the Arts Council, the GLC and Pilgrim Trust went “missing” with little or no explanation being offered. Flash forward to 2020 and the global pandemic transforming the world into an unknown environment. Across the UK, venues large, small, and downright peculiar had to find ways to support themselves and their artists through a crisis that was never fair or predictable and all too many found themselves unable to continue delivering magnificent, rowdy and rebellious noise as the pandemic released us from its grip. For many venues and cultural projects, salvation came in the form of donations and grants from organisations such as The Music Venues Trust, the COVID Recovery Fund, and The Arts Council.

The first rumblings of jass (later to be renamed, jazz) in the UK came from a collision of popular cultures found on both sides of the Atlantic. From the ‘King of Ragtime,’ Scott Joplin, and the 'Maple Leaf Rag' came a new and distinctive musical genre developed primarily by black musicians. It drew from ragtime, blues and popular songs and was based principally on improvisation. A thriving community of musicians, including cornetist Charles 'Buddy' Bolden (born in 1877 and romantically credited as 'the first jazzman') and later players such as cornetists Joe 'King' Oliver and the young Louis Armstrong had established New Orleans as the home of jazz by 1920. The first jazz record is often considered to be 'Dixie Jass Band One Step/Livery Stable Blues,' recorded by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band in February 1917.

By the mid-1920s jazz was a thriving preoccupation in British culture with the publication of the magazine Melody Maker in 1926 and the BBC's first broadcasts (principally of dance music) helping to build its popularity. Records were available too, though the earliest to reach Britain from America were mainly by white artists such as cornetist 'Red' Nichols and trombonist 'Miff' Mole. But recordings by Afro-American players, including Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, quickly followed, and it was Armstrong whose solo recordings from 1925 with his Hot Five and Hot Seven definitively established jazz as a soloist's art rather than an ensemble-based music as most of the early New Orleans jazz had been.

The arrival in London of seminal American musicians, especially Louis Armstrong (1932) and Duke Ellington (1933), inspired the British jazz community, generating excited publicity, popular and professional interest – and occasional controversy. The No 1 Rhythm Club opened in London in June 1933 and over the next few years, many more such rhythm clubs were formed throughout the country. They fostered interest in (and serious intellectual consideration of) jazz by holding record recitals, discussions and sometimes musical performances for their members.

During the Second World War entertainment was needed to help bolster morale. The danceable, virtuoso music of the Swing Era (1935–45) was provided – for both American and British ears – by famous bandleaders such as Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Harry James, Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, and Glenn Miller. Thanks to radio, records, film and vibrant publicity in the popular press, they were the equivalent of today's rock stars.

The 1950s was the final decade in which jazz flourished as a broad youth culture. It produced many British solo stars – traditionalists on one side, modernists on the other – and bandleaders. During the 1950s immigration into Britain brought an influx of players from the Caribbean. Amongst others, Joe Harriott, flautist/saxophonist Harold McNairn and trumpeter Dizzy Reece (all from Kingston, Jamaica) joined a West-Indian population of British jazz performers that already included trumpeter Leslie 'Jiver' Hutchinson (father of singer Elaine Delmar), pianist-singer Cab Kaye, bassist Coleridge Goode, and saxophonist Bertie King.

From its inception in New Orleans bordellos at the dawn of the 20th century, jazz has never stood still. Jazz has always been fuelled by modern, contemporary artists, and young jazz musicians seeking new modes of expression. Indeed, the future of jazz has always reflected the changing times that have shaped its creators’ sensibilities.

One of the defining aspects of the new UK jazz scene is the sense of collaboration and community among the musicians. Artists often work together on different projects, share stages, and support one another’s creative endeavours. This collaborative spirit has fostered a tight-knit and diverse community of musicians, with each artist bringing their unique influences and experiences to the table.

In the second decade of the 21st Century, the music whose essence is improvisation is prospering again: a younger generation of listeners have turned to pathfinding figures like Robert Glaser and Kamasi Washington, who have helped jazz reclaim its relevance. With broader exposure, young jazz musicians are passing on the music’s DNA and keeping it alive – and ever-changing – by marrying it with other types of music.

Venues and festivals such as London’s Total Refreshment Centre, Jazz re:freshed, and the Love Supreme Jazz Festival have played crucial roles in nurturing this community and providing a platform for emerging talent. Furthermore, record labels like Brownswood Recordings and International Anthem have championed the new wave of UK jazz artists, enabling their music to reach global audiences.

Photography by Eliza Mazzuca

Notes and Credits:

**At the time of publication, Ronnie Scott’s continues to decline requests for comment or clarification. **

Digby Fairweather, The Jazz Centre UK

The Evening Standard

1989 their general secretary (the late) Maurice Jenningsexpressed the view in a letter to the now-defunct ‘Jazz Services’ company that “jazz musicians are a wandering tribe who will forcibly resist any form of corporate organisation”.This prompted a swift response from me to Maurice that: “if such a viewpoint was held about mental illness we would still have the Bedlam hospital in London”. - Digby Fairweather, The Jazz Centre UK

Activism and Accessories: What are you wearing?

Now the red carpet has been rolled back and the time-honoured dissection of dresses and drama has passed; The Academy Awards are once again at the centre of a political and personal debate. In 2022, the controversy centred around the violence perpetrated on stage as Will Smith assaulted comedian Chris Rock in front of a global audience. This year, Oscar ceremony attendees used the awards as a platform to unite and call for immediate action to halt the conflict and ongoing atrocities unfolding in the Israel-Hamas war.

Now the red carpet has been rolled back and the time-honoured dissection of dresses and drama has passed; The Academy Awards are once again at the centre of a political and personal debate. In 2022, the controversy centred around the violence perpetrated on stage as Will Smith assaulted comedian Chris Rock in front of a global audience. This year, Oscar ceremony attendees used the awards as a platform to unite and call for immediate action to halt the conflict and ongoing atrocities unfolding in the Israel-Hamas war.

As a sign of solidarity and support, an accessory prominent on Sunday's red carpet was a red pin featuring a hand with a black heart in the middle. Celebrities like Billie Eilish, Ramy Youssef and Mark Ruffalo wore the pins in support of Artists4Ceasefire, a group of advocates and artists that opposes the conflict in Gaza.

Inside the ceremony, several of the night’s nominees, including Selma director Ava DuVernay and Poor Things actor Mark Ruffalo, as well as Best Original Song winners Billie Eilish and Finneas O’Connell, were seen sporting pins in support of Artists4Ceasefire, an organisation calling for a ceasefire in Gaza and Israel and humanitarian aid to reach Palestinian civilians.

The red pins feature an image of an outstretched hand.

Speaking to Variety on the red carpet, Poor Things star Ramy Youssef said: “We’re calling for an immediate, permanent ceasefire in Gaza. We’re calling for peace and lasting justice for the people of Palestine.”

Anatomy of a Fall actors Milo Machado Grenier and Swann Arlaud were also seen wearing pins bearing the Palestine flag.

On Sunset Boulevard, riot police were present as demonstrators gathered to protest, reportedly yelling “Free Palestine” and “Let’s shut it down” on the outskirts of the venue. The beginning of the ceremony was delayed by around five minutes due to the protest.

An open letter signed by over 400 artists through the Artists4Ceacefire organisation was sent to US President Joe Biden last year. Among those lending their name to the letter were Jessica Chastain, Quinta Brunson, Richard Gere, Cate Blanchett, Lupita Nyong’o, Mahershala Ali and Barbie nominee America Ferrera.

The letter, available to read on Artists4Ceacefire’s website, reads: “We come together as artists and advocates, but most importantly as human beings witnessing the devastating loss of lives and unfolding horrors in Israel and Palestine. More than 30,000 people have been killed over the last 5 months, and over 69,000 injured – numbers that any person of conscience knows are catastrophic.”

Written by Daisy Sells.

Richard Shotwell/Invision/AP

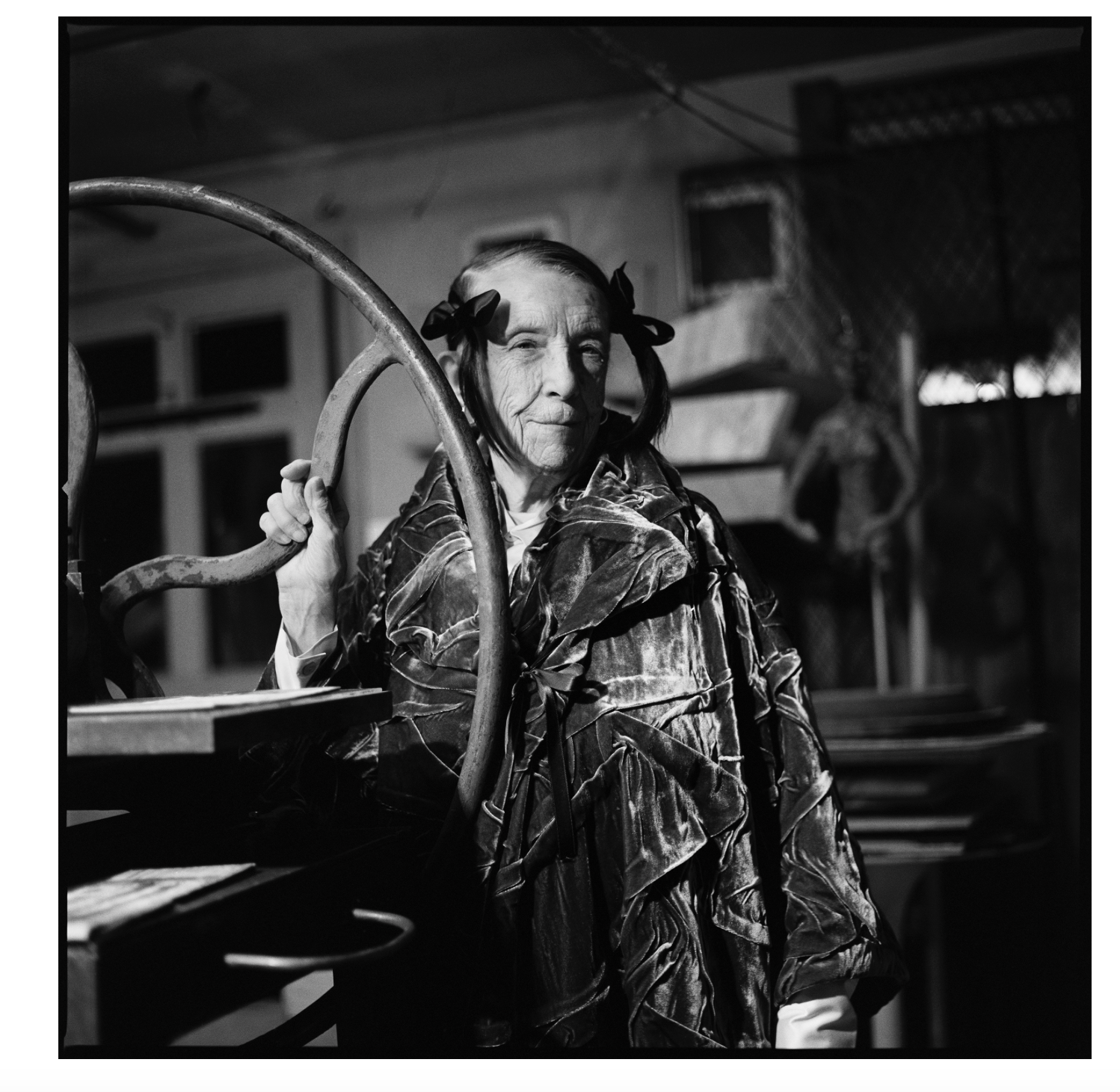

Iris Apfel: “More is More and Less is a Bore.”

Iris Apfel, an interior designer and fashion celebrity, with her larger-than-life personality and unmistakable flare, has died aged 102. Through her words, she guided us to embrace our uniqueness and to revel in the joy of self-expression.

Iris Apfel, an interior designer and fashion celebrity, with her larger-than-life personality and unmistakable flare, has died aged 102. Through her words, she guided us to embrace our uniqueness and to revel in the joy of self-expression.

“More is more and less is a bore.”

“I don't have any rules, because I'd only be breaking them."

"If your hair is done properly and you're wearing good shoes, you can get away with anything."

"I'm not interested in age. People who tell me their age are silly. You're as old as you feel."

"When you don't dress like everybody else, you don't have to think like everybody else."

"You can't learn style. It's like writing—you either have it or you don’t."

"I like things that are not too perfect, that have a little crack."

"To me, colour is like music. You have to learn to listen to it."

"You have to be interested. If you're not interested, you can't be interesting."

"If you're lucky enough to have something that makes you different from everybody else, don't ever change."

"I don't see anything so wrong with a wrinkle. It's kind of a badge of courage."

"I don't have time to be bored; there's so much to do."

"I've always thought of accessories as the exclamation point of a woman's outfit."

"The key to style is learning who you are, which takes years. There's no how-to road map to style. It's about self-expression and, above all, attitude."

The Inevitable Demise of Mainstream Fashion Publications: A Surrealist Exploration

This essay delves into the multifaceted reasons behind the decline of mainstream fashion publications, drawing upon the surrealistic movement as a lens through which to understand their inevitable demise.

Mainstream fashion magazines have long reigned as cultural arbiters, dictating trends, shaping perceptions of beauty, and influencing consumer behaviour. Yet, in recent years, these glossy publications have faced an existential crisis, grappling with declining readership, shifting consumer habits, and the relentless march of social media. This essay delves into the multifaceted reasons behind the decline of mainstream fashion publications, drawing upon the surrealistic movement as a lens through which to understand their inevitable demise.

Surrealism: Unleashing the Subconscious

Surrealism developed out of the ashes of Dadaism. Dadaism emerged during World War One as a response to the absurdity and chaos of the time and rejected traditional artistic conventions. It was characterised by irrationality, anti-bourgeois sentiments and an emphasis on the nonsensical. Surrealism, which developed in the 1920s, was built upon Dadaist principles but focused more on exploring the unconscious mind and dreams. Surrealist artists sought to channel the irrational and subconscious through techniques like automatism, which allowed for the spontaneous expression of thought without conscious intervention.

The Rise and Fall of Mainstream Fashion Publications

The ascendance of mainstream fashion publications in the 20th century paralleled the use of consumer culture and the democratisation of fashion. From Vogue to Elle, these magazines wielded immense influence, shaping not only what we wore but also how we perceived ourselves and others.

However, the digital revolution and changing consumer preferences have dealt a severe blow to the domination of mainstream fashion publications. The proliferation of online platforms and social media channels has democratised fashion discourse, allowing for a greater diversity of voices and perspectives. Moreover, growing awareness of issues such as body positivity, diversity and sustainability has prompted many consumers to question the values espoused by mainstream publications, leading to a decline in readership and relevance.

Surrealism’s Critique of Consumer Culture

At its core, Surrealism represented a radical critique of bourgeois society and consumer culture, challenging the ethos of materialism, conformity, and rationality. Surrealist artists sought to expose the underlying contradictions and absurdities of modern life, using their work to subvert dominant narratives and disrupt conventional modes of thought.

When applied to fashion, Surrealist principles offer a potent sense through which to deconstruct the facade of mainstream magazines. By decontextualising fashion imagery and challenging linear narratives of fashion trends, Surrealist-inspired critiques can reveal the underlying tensions that underpin consumer culture.

The nature of a fashion publication is to predict, narrate and determine trends. In doing so, however, they rather shoot themselves in the foot. Crawforth (2004) states about the fashion magazine: “…its contents necessarily out of date the moment they come into existence in print, and its function shifting over time from prophesying the modes of the future to serving as historical documentation of the past…”

Thus identifying a poignant issue, in determining the trends to the masses fashion magazines normalise them, and thus they are no longer trendy. In vain, the publication highlights the next trend and the cycle repeats. Vogue itself highlighted this flaw while unintentionally demonstrating the temporal nature of surrealist art.

The cover of Vogue’s June 1939 issue was an image of Salvador Dali’s work. The issue opens with an editorial by Edna Woodman Chase, accompanied by an illustration bearing many similarities to the work of a surrealist. Chase’s awareness of the boundaries of surrealism is apparent: ‘Don’t try to read Surrealist symbolism into this photograph. There’s plenty of real Surrealism in this issue to puzzle over: Dali’s enigmatic cover…his interpretation of the new chemists’ colours in bathing suits. The above is just a fantastic skirmish of ours.’

Here Chase makes sure the difference is clear: that she believes Dali’s cover was truly surrealistic and that the illustration similar to the surrealists’ work was not. Chase failed to make note of that, Vogue, by publishing Dali’s work in the form of a magazine, was limiting it to a temporary and disposable existence, the sort of existence Surrealists hoped for their work.

Vogue did not understand that in doing so they were also reflecting their fate. The fashion magazine represents a truly perishable and ephemeral symbol for the Surrealist movement and Vogue’s attempt to liken their issues to surrealistic work predicted their demise.

An Alternative Approach: zines

So, how does this apply to fashion press today?

In the wake of the pandemic and amid a climate crisis people have been reevaluating their moral relationship with consumption. An interesting development from this aspiration of change is the rise of the zine. A noncommercial often homemade or online publication usually devoted to a specialised and often unconventional subject matter - the zine can be seen to represent the shift away from mass production, overconsumption and the need to be ‘on trend’, all of which are ideologies that surrealists themselves strived to achieve.

Though it could be argued that zines themselves are becoming a trend, each is set within its own subculture, each has its own audience and niches that it caters towards, and, what I believe to be most important, none are reproduced to the extent that they can be deemed as “trendy”.

What happens when large fashion publications begin to imitate the aesthetic of zines? To put it simply, they won’t achieve what they hoped to. This idea can be paralleled to Vogue’s imitation of surrealism. Imitating a subculture does not make you part of that subculture as the imitation of surrealism does not make you a surrealist. Attempting to increase their audience by replicating the aesthetics of a zine does not change the foundations that mainstream fashion publications have been built on.

To conclude, the demise of mainstream fashion publications finds a provocative parallel in the surrealist movement’s critique of consumer culture. Surrealism, with its emphasis on the subconscious and its challenge to bourgeois norms, offers a lens through which we can understand the unravelling of traditional fashion media. Just as surrealists sought to expose the contradictions of their time, mainstream fashion magazines, in their quest to dictate trends, inadvertently hasten their own irrelevance.Mainstream fashion magazines have long reigned as cultural arbiters, dictating trends, shaping perceptions of beauty, and influencing consumer behaviour. Yet, in recent years, these glossy publications have faced an existential crisis, grappling with declining readership, shifting consumer habits, and the relentless march of social media. This essay delves into the multifaceted reasons behind the decline of mainstream fashion publications, drawing upon the surrealistic movement as a lens through which to understand their inevitable demise.

Written by Phoebe Violet.

References:

Crawforth, H. (2004). Surrealism and the Fashion Magazine. American Periodicals, 14(2), 212–246. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20770930